By Miguel Pires da Rosa from Braga, Portugal (Recycle) [CC BY-SA 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

By Miguel Pires da Rosa from Braga, Portugal (Recycle) [CC BY-SA 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Last week I wrote about dishwashing as a spiritual discipline. By channeling the wise words of a Buddhist monk and a medieval master, we can “wash each dish as if it were the baby Jesus.” We introduce tenderness into a chore that usually invites frustration.

Today—dishwashing as a moment of delight.

We begin by doing the dishes as a form of imitatio Christi. Surprising—unless you’re familiar with the medieval way of approaching Jesus.

In the fifteenth century, Jean Gerson, chancellor of the University of Paris, wrote about the boyhood of Jesus:

Thus Christ was subject, as he was to you, Mary and Joseph,

What kind of subjection did he wish for himself?

Was he not showing obedience in your midst, as one who rightly serves?

Carefully and often he lights the fire and prepares the food;

He does the dishes and fetches water from a nearby fountain.

Now he sweeps the house, gives straw and water to the donkey.*

We do the dishes because Jesus first did them for his parents. Is it any wonder I love the Middle Ages?

This tidbit about Jesus is, as you’ve doubtlessly realized, extra-Biblical. Gerson uses his imagination to bring to life the Bible’s brief statement that the boy Jesus was obedient to his parents (this was after Jesus was “lost” for three days in Jerusalem–see Luke 2:51).

Gerson’s poem represents the medieval imagination at its finest. Like Ludolph of Saxony’s Life of Christ (discussed in my previous post), it paints a picture of Jesus meant to delight us and to invite us into his life.

This kind of imagination doesn’t often figure into modern approaches to Jesus. We usually stick to what we know. But I was pleasantly surprised when my Sunday school class recently veered off our assigned topic (Jesus’ public ministry) and began discussing, in a very imaginative way, what the Holy Family’s life might have been like. What was it like for Mary, raising Jesus and knowing–but maybe not knowing–who he was and what he was destined to do? What opinions did the Holy Family’s neighbors have about the boy Jesus? Did they think he was exceptional, and maybe a bit peculiar, without realizing that he was the Messiah?

This discussion filled me with delight! It was, for a moment, like being in the Middle Ages, when church officials and laypeople alike loved talking about the “lost years” of Jesus’ life.

What do you think about this kind of discussion? Is it legitimate to “flesh out” Jesus’ obedience and other events in his life? Have you yourself ever wondered about all those moments we know nothing about?

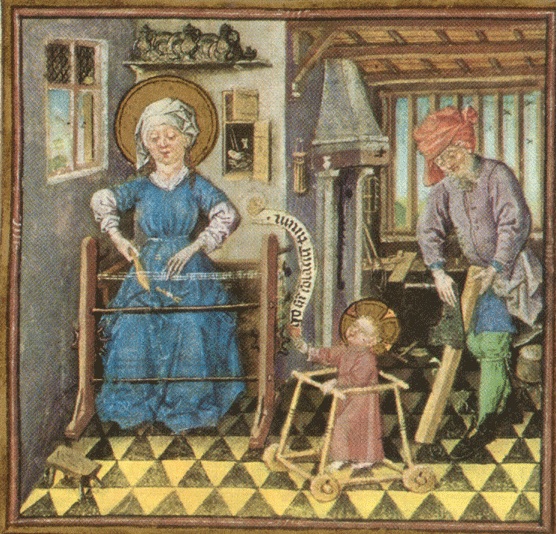

Here’s another moment. In this miniature from the Hours of Catherine of Cleves (ca. 1440), Jesus is shown taking steps in a baby walker. (This is a few years before he learned to do the dishes!) Nearby, Mary weaves while Joseph planes a piece of wood. This scene of delightful intimacy may have been intended to help the book’s owner, the Duchess of Guelders, prepare for her (hoped-for) role as mother.

By Clèves Master [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

There’s some theology behind these wonderful little scenes. Gerson himself said there is no better way to soften hard hearts than to let faith see God acting as a child. He wanted to help Christians delight in the boy Jesus and to affirm that God became human—a small human with parents, chores, and child-like faith. Gerson’s imagination is in service of the incarnation.

I think we could use a little more imagination in our faith today. We are so good at studying the Bible. We parse its meaning verse by verse and even word by word. We defend our beliefs with arguments and analysis. We listen to three-point sermons that tell us how to live.

Sometimes, this approach leaves me exhausted. I feel like I’m drowning in meaning and interpretation. I recently turned down an invitation to join a Bible study because, frankly, it seemed too labor intensive. It involved too much homework, too many workbooks, and too many lectures. I love God’s word, but sometimes, instead of study guides, I need to be guided to some lighter moments. I need to enjoy my faith and to delight in who Jesus was and is. “God laughs into our soul and our soul laughs back into God,” writes Richard Foster about experiencing delight in our Lord.

Gerson’s poem opens the door to a moment of delight, one I can experience even at the kitchen sink. Thanks to this medieval chancellor–and that wonderful discussion in my Sunday school class–I can no longer do the dishes without imagining the boy Jesus scrubbing away at the nearby fountain. I think of the incarnation, which is good. I remember that Jesus participated fully in the messiness of life. Very theological.

But more than all that, I smile. I like thinking that God did the washing up, in more ways than one.

*This quotation and other information about Gerson are from Brian Patrick McGuire, “When Jesus Did the Dishes: The Transformation of Late Medieval Spirituality” in The Making of Christian Communities in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, ed. Mark Williams (London: Anthem Press, 2005), pp. 131-152.