“The kingdom of self is heavily defended territory.” – Eugene Peterson

I usually think whatever I’m doing is soooooo important. I have my schedule. I guard my time. I’ve made my plans. Woe to the one who decides to burst in on them!

I especially worry about being interrupted when I’m working — which means writing, thinking, dreaming. Writing is often how I pray. It’s when I sort through my ideas about God and praise him in the best way I know how.

Except when it’s not the best way.

In the mid fourteenth century, an Augustinian canon named Walter Hilton wrote a treatise addressed to a wealthy layman. The recipient of this treatise loved God and seemed to feel guilty that he was not a monk or a priest. Hilton’s response is wonderful. Embrace the life you have, he says. And that means embrace interruptions.

A contemplative quality of life is fair and fruitful, and therefore it is appropriate to have it always in your desire. But you shall be in actual practice of the active life most of the time, for it is both necessary and expedient.

Therefore, if you are interrupted in your devotions by your children, employees, or even by any of your neighbors, whether for their need or simply because they have come to you sincerely and in good faith, do not be angry with them, or heavy handed, or worried — as if God would be angry with you that you have left him for some other thing — for this is inappropriate, and misunderstands God’s purposes.*

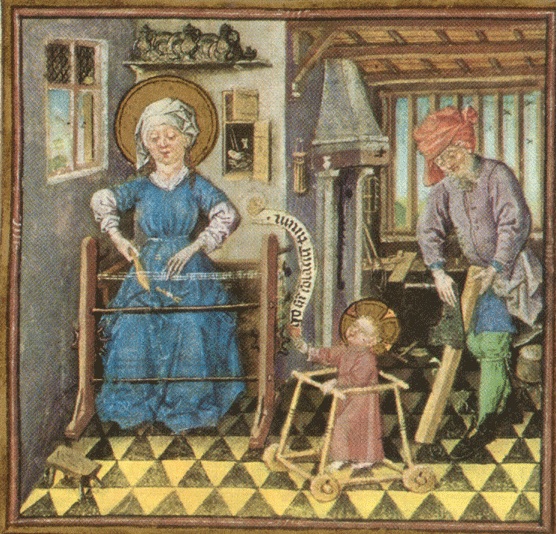

![A medieval cellarer--a man leading "the active life." Creator:Monk of Hyères Cibo [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons](http://www.lisadeam.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Medieval-cellarer-300x265.jpg)

How often have I gotten angry about these kinds of interruptions? Or worse, how often have I told my children, “Just a minute — I’ll be right with you,” never taking my eyes from the computer screen?

In Hilton’s advice I find a gentle reproof. Do not be heavy handed. Don’t be so worried! And I find a “spirituality of interruption.” It tells me: I don’t leave my devotions when I take my children into my arms. This interruption is my devotion. I don’t leave my work when I assist someone. The neighbor who needs me is my work. This spirituality is, frankly, a challenge.

Recently I’ve seen other thoughtful people wrestling with this idea. A recent post by Ken Chitwood describes those moments when someone, perhaps someone unknown, has been “thrust into our hectic schedule” as momentary vocations — they are God’s invitation to join him in caring for the world. “Momentary vocation” is a lovely term for interruption, isn’t it? God puts these interruptions, er, vocations right under our noses, if we’re not too busy building our kingdoms to notice them.

I’m coming to believe that God has written these interruptions into my schedule, as immovable and sacred as fixed-hour prayer. I imagine God adding them to my calendar when I’m not looking. “Won’t she be surprised!”

Yes, she usually is.

Most of us aren’t monks. But that doesn’t matter: our active lives are sacred callings. I’m learning that there are no interruptions to prayer. Just different kinds of prayer.

*Toward a Perfect Love: The Spiritual Counsel of Walter Hilton, trans. David L. Jeffrey (Portland, OR: Multnomah Press, 1985), p. 18.

Lisa’s book, A World Transformed: Exploring the Spirituality of Medieval Maps, is on sale (Kindle version) for $2.99 for a limited time. Check it out and share the news!